"Digital identity" has replaced blockchain to become 2019’s new tech-based solution to revolutionize compliance functions from anti-money laundering (AML) to audit. However, given the recent involvement of Estonia’s digital identity network in the Danske Bank money laundering scandal, the question of how to ensure adequate financial crimes oversight has taken center stage.1 This aside, the potential of digital identity still appears to be endless which further highlights the importance of engaging financial crimes professionals early on in the building stages so that a scalable and secure solution is deployed.

What is digital identity?

The definition of digital identity can vary depending on the context. For example, digital identity traditionally refers to an amalgamation of all available attributes and information that can bind an online persona to a physical person.2 Taking a step back, one could also broaden this definition so that it is not reliant on the internet by replacing the word “online” for the verbiage “available on computer systems.”3 The distinction between online and computer systems becomes increasingly important as the conversation around digital identity becomes more formalized. Entities interested in issuing digital versions of identity cards, or relatively static pieces of identifying information to a particular person, would be less concerned with the amalgamation of an individual’s online user history as they would with being able to securely store, transmit and trace particular pieces of information prescribed to an individual by a trusted entity, such as a government agency.

Digital identity is data about persons stored and accessible through computer systems that closely link to their civil and national identities

In looking at digital identity from the vantage of uploading physical identification documents to a computer-based system accessible by the internet, the definition of digital identity would change from the aforementioned to something more akin to the following: digital identity is data about persons stored and accessible through computer systems that closely link to their civil and national identities.4 This more formal definition of digital identity will be referred to as “digital identification” for the remainder of the article.

The definitions provided for digital identity and digital identification exclude exploration of digital identity from a philosophical perspective due to the scope of this article. However, there are a few relevant points related to digital identity and one’s personality that should be mentioned. First, it is widely acknowledged that the internet and its perceived anonymity—along with certain aspects of actual anonymity realized through encryption technology—allow a particular user to foster multiple personas online as opposed to their real-life environment. This autonomy can create challenges for entities seeking to establish standards for instant verified identification; however, the cumulated data can assist with identification of a particular individual via investigation. Second, it is important to note the ways in which individuals have begun to re-examine their self-existence, self-expression and self-identification in a digital age. This is an important realization when attempting to mitigate privacy risk as it highlights the heightened scope of information—and sensitivity to that information by underlying customers—that an issuing entity of digital identification would have exposure to should a breach be successfully executed. This risk is compounded as a digital identification network brings on more participants across various industry sectors, increasing the potential for oversight of a particular user’s lifestyle above and beyond financial transactions.

Lastly, it is important to note that digital identification differs from digital authentication, which is the act of validating one’s self when trying to access an account or device. For example, logging into one’s email account through inputting a password would be a form of digital authentication. In addition, leveraging biometric identifiers, such as fingerprints or retina scans, would be considered digital authentication. To recap, digital authentication answers the question “is that you?” while digital identification is intended to answer the question “who are you?”5

Digital Identification Networks

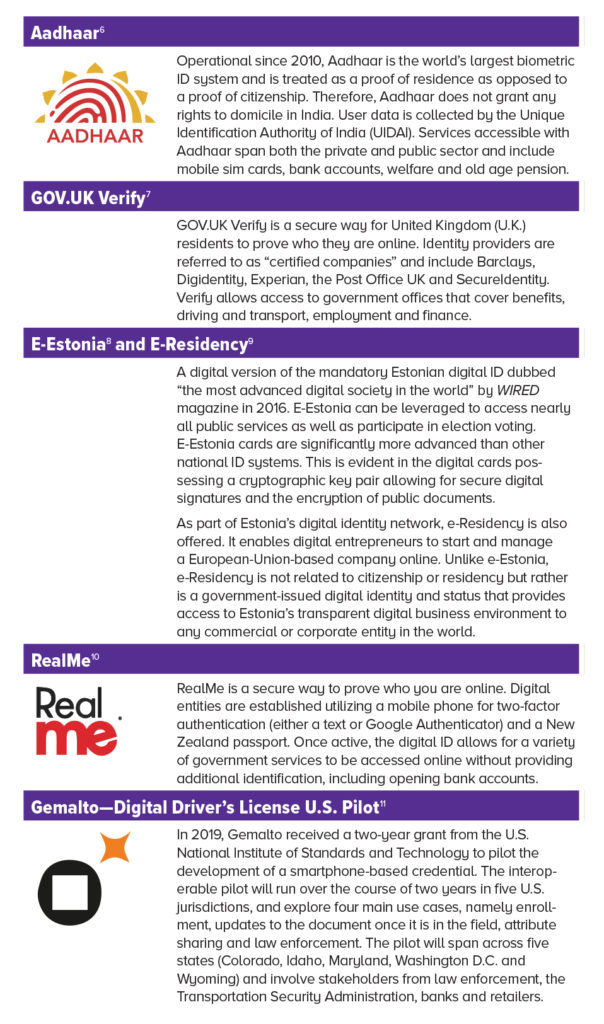

There are several digital identification networks operational today across public and private sectors in many respective jurisdictions. These platforms vary in their usability, as well as the technology, which underpins them. Some networks utilize a traditional database while others opt in for a decentralized blockchain and there are even hybrids in between. To the left is an overview of just some of the more prolific networks in operation.

Public Sector

Several digital identification networks have been launched by many governments worldwide that seek to address different scenarios, from increasing the efficiency and accuracy of delivering social services to the issuance of digital driver’s licenses. Many of the platforms, such as India’s Aadhaar ID system and New Zealand’s RealMe system, also allow opening of bank accounts. While the following digital identification schemes are largely funded by the public sector, many are in partnership with private enterprises that specialize in the technology required to execute a digital identification system.

Private Industry

The private industry is also looking to issue digital identification, which is interesting given that identity has historically been largely monopolized by governments. However, as the world continues to experience what eminent consumer psychologist Russell W. Belk at Canada’s York University refers to as the “dematerialization” of many goods and services in favor of digital representation, businesses are left managing how they interact with their customer base across this new digital landscape.12 In addition, advancements in data-sharing utilizing encryption, particularly through the advent of blockchain-based technology, has offered up potential tools to realize a privately managed digital identification solution.

Impact on Financial Services and Financial Crime

The financial service industry is at the forefront of the digital identification revolution in both the public and private sectors. For example, deposit-taking institutions, i.e., banks, are simultaneously being engaged as data providers in publicly run digital identification networks, as is the case with the GOV.UK Verify platform, while others are collectively collaborating amongst their industry peers to stand up their own solution, as is the case in Canada’s Verified.Me network. Regardless, banks are and will be a major part of the digital identification conversation for the foreseeable future. This level of multistakeholder engagement makes sense given the trusted nature of banks within the broader economy. Furthermore, many banks have acknowledged that the issuance of a digital identification network is no easy task and requires significant collaboration and strong partnerships.

Cross-Industry Benefits

The advantages of launching a digital identification network to an FI stretches across various arenas such as increasing revenue, elevating the customer experience and enhancing regulatory adherence. The McKinsey Global Institute conducted a study in April 2019 that identified six key types of interactions that a digital identification solution facilitated with institutions both public and private. Although not specific to finance, the key types identified had varying degrees of relevancy to FIs, such as the facilitation of transactions between asset service providers and owners, as well as enhancing the relationship between consumers and commercial providers of goods and services.16 Furthermore, the McKinsey report highlights the following examples of potential value created through leveraging digital identification solutions:

- Time and cost savings

- Increased financial inclusion

- Increased agriculture productivity

- Fraud reduction17

It is estimated that approximately 1 billion people worldwide do not have a formal way to prove their identity. The inability to identify oneself creates barriers when trying to access education, healthcare and economic opportunities in general.18 In addition, the inability to be identified increases the possibility for an individual to be exposed to criminality whether as a perpetrator or victim. This is evident in the migrant crisis Europe has been grappling with over the past several years, of which many of the individuals entering European countries are undocumented. Furthermore, smugglers and traffickers thrive in this type of environment given the anonymity it presents.

This macro view of identity begins to paint a picture of the economic value and social good a digital identity can create if it could be issued through nongovernmental, intergovernmental or public-private partnership collaborations such as the ID2020 initiative.

Benefits to Financial Institutions

In narrowing the scope to FIs, it can be argued that the primary current benefit of participating in a digital identification network is to be able to identify a customer accurately through digital channels for a cost lower than what it would take to execute through traditional processes. However, in the not-too-distant future, the primary benefit of digital identity networks could shift toward monetizing the identification process through transforming FIs into “trust brokers” via their contributions to digital identification networks. The combination of these two benefits would result in an overall increase in revenue via lower operating costs and new profit streams, all while potentially increasing the effectiveness of financial crimes mitigation via a streamlined approach to know your customer (KYC) procedures and increased auditability.19

A further breakdown of the benefits of digital identity requires a level setting of what it means to identify and authenticate someone within a traditional banking context. The following quick reference chart highlights primary components of what the action of identifying and authenticating entails:

The process of identifying requires specific attributes provided by trusted sources (e.g., government registries) to be linked to a person (entity or individual). This process is largely regarded as KYC within AML. Once this is completed, compliance programs—particularly AML units—require identities to be easily accessible and traceable during the time for which the relationship with the customer exists. The process of matching attributes and tracing identity is costly and time consuming. Traditional methods for completing such tasks require significant resources in both people and technology. In addition, this process is completed internally and its value is derived almost entirely from avoiding financial crimes risk—meaning there is no monetary value created in conducting this exercise but rather a precautionary exercise to ensure regulatory compliance and financial stability.

In moving to a digital identification solution, much of the friction encountered in the traditional scenario become streamlined as the partnership between network participants begins to reduce associated costs and also provide revenue to those banks that still complete the identifying process. In looking forward, if a particular digital identification platform were to experience a “network effect” of multiple service providers and reporting entities joining the ecosystem for cheaper access to reliable and secure KYC information, revenue would increase for those that still undertook the responsibility to compile this information in a traditional sense. However, even if a bank or other participant decided to be a contributor via traditional KYC compilation, it does not preclude them from also relying on the network for identification purposes. Digital identification networks could revolutionize how a bank identifies customers and also how the act of identifying is valued both inside and outside of its purview.

When pivoting to the concept of authentication, the conversation becomes a bit less certain. While digital identification networks can be quite efficient and secure the question, how to ensure the appropriate persons have access to the network can be somewhat challenging. Furthermore, the question of liability arises when the incorrect individual, or bad actor, authenticates themselves through a digital identification network participant who was not the original entity that onboarded them by using hard copies of government-issued identification, resulting in a loss. These are just two areas of risk that will be further explored and weighed against the aforementioned benefits.

Risks to Financial Institutions

Digital identification does not come without its share of risks, which can be largely segmented into the following categories:

- Data security

- Governance

- Methods of authentication

- Transaction monitoring

- Liability

The first two risks, data security and governance, are centered around privacy and consistent with many of the risks banks have to mitigate on a daily basis today. However, as mentioned earlier managing privacy in a digital identification network heightens associated risks given the inter entity nature of the platform, as well as the ability for the platform to be leveraged for transactions beyond those specifically tied to financial exchanges. This also highlights the need for strong governance and supportive governmental legislation, as in the case of the U.K. and India, to ensure standards on how data is utilized and to provide a way out of the digital identification network.

The final three risks indicated above, methods of authentication, transaction monitoring and liability, tie-in closer to financial crimes risks. While digital identification networks can enhance the security, transmission and traceability of identifying information, risks still exist through the potential of a false or fake identity being uploaded into the system. Synthetic identification, the combination of real (usually stolen) and fake information to create a new identity,20 and basic fake identification are just two possible attack vectors aimed at the onboarding process of digital identification networks. In addition, there is also the potential for a bad-actor employee to upload a fake identity into the system. This bad-actor scenario is realized on the traditional governmental side from time to time through departments of transportation issuing false driver’s licenses via corrupt employees.

Safeguarding against malicious behavior, such as attempting access to the digital identification network, will most likely involve transaction monitoring scenarios and thresholds. This will ensure that an individual utilizing digital identification verification via a third-party user of KYC information does not incur significant financial loss for which the originating entity that processed the individual could be liable. Possible security mitigants could include the following:

- Limiting access to digital identification networks for accounts operational for a minimum time period (e.g., six months)

- Limiting access to digital identification networks to customers who have minimum assets or transaction amounts passing through their accounts

- Imposing credit limits or limited access to high-risk products for those onboarded solely via digital identification networks

- Monitoring the number of times a digital identity is utilized over a given time period

- Monitoring the types of institutions that request identification verification

- The last two bullets may infringe on privacy depending on the rules set up for a digital identification network

- Increased transaction monitoring for accounts open solely through digital identification networks by traditional financial crimes programs (AML, fraud, etc.)

- Policy that includes the requirement for hard copy identity to be utilized for extremely high-risk products or services

- Limiting access to digital identification networks to entities (individuals or commercial) that have vested interest in the respective country operating the network (This is a challenge the country of Estonia recently encountered that was a major part of the exploitation of Danske Bank by Russian launderers.21)

Safeguarding against malicious behavior, such as attempting access to the digital identification network, will most likely involve transaction monitoring scenarios and thresholds

Conclusion

Digital identification solutions appear to offer more to the fight against financial crimes than they do to hinder them. Advancements in the way information is compiled, stored, transmitted and traced truly do streamline many of the regulatory requirements of a financial crimes program, including audit functions. Furthermore, the potential to transform some of the functions into revenue generating units, without sacrificing integrity, is equally as exciting. However, as with any new technology, digital identification networks require a combination of modified and new tools to mitigate the risks that come part and parcel.

Standardized risk-mitigating policies for network participants, such as transaction monitoring rules and scenarios, are just part of the multifaceted approach that is required to guarantee success. Another major part of this success is contributed by transparent legislation that uploads privacy and a right to opt out of a digital identification network, as well as how data can be utilized and accessed amongst network participants. Lastly, the formation of public-private partnerships in Canada, such as the Digital ID & Authentication Council of Canada,22 round out what is suggested when considering the deployment of a digital identity network.

In looking ahead, one can hypothesize about the additional road mapping and strategy that is required, such as building out interoperability between different digital identification networks, and considering possible technological changes, such as open-source block chain technology. However, in turning back to the present, digital identification solutions appear to be a worthwhile venture for any trusted institution to pursue as its potential and importance is too significant to ignore.

- John O’Donell, “Dirty money risks encroach on Estonia’s digital utopia,” Reuters, February 1, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-estonia-danske-digital-insight/ dirty-money-risks-encroach-on-estonias-digital-utopia-idUSKCN1PQ3UU

- Avi Turgeman, “Demystifying Digital Identity: What It Is, What It Isn’t And What I Can Be,” Forbes, November 15, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/11/15/ demystifying-digital-identity-what-it-is-what-it-isnt-and-what-it-can-be/#1ec9eb292af1

- “Digital identity,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_identity

- Ibid.

- Avi Turgeman, “Demystifying Digital Identity: What It Is, What It Isn’t And What I Can Be,” Forbes, November 15, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/11/15/ demystifying-digital-identity-what-it-is-what-it-isnt-and-what-it-can-be/#1ec9eb292af1

- Unique Identification Authority of India, https://uidai.gov.in/

- “GOV.UK Verify overview,” GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ introducing-govuk-verify/introducing-govuk-verify

- “e-identity” e-estonia, https://e-estonia.com/solutions/e-identity/id-card/

- “The new digital nation,” Republic of Estonia e-Residency, http://e-residency.gov.ee/

- “The easiest and most secure way to prove your identity online,” RealMe, https://www.realme.govt.nz/

- “Digital Driver’s License U.S. Pilot,” Gemalto, https://www.gemalto.com/ddlpilot

- Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, “How different are your online and offline personalities?” The Guardian, September 25, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/2015/ sep/24/online-offline-personality-digital-identity

- “Your identity in your control,” Verified.Me, https://verified.me/

- “Digital Identity,” Mastercard, https://www.mastercard.us/en-us/issuers/products-andsolutions/mastercard-digital-identity-service.html

- “Unleashing Trust, Identity and Credibility networks for humanity.” Shyft, https://www.shyft.network/

- “Infographic: What is good digital ID?” McKinsey Digital, April 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/ infographic-what-is-good-digital-id

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “ID2020: Digital Identity with Blockchain and Biometrics,” Accenture, https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-blockchain-id2020

- “Synthetic Identity Theft,” Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/syntheticidentity-theft.asp

- John O’Donell, “Dirty money risks encroach on Estonia’s digital utopia,” Reuters, February 1, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-estonia-danske-digital-insight/ dirty-money-risks-encroach-on-estonias-digital-utopia-idUSKCN1PQ3UU

- “About Us,” DIACC, https://diacc.ca/about-us/