ACAMS Today had the opportunity to interview Cameron "Kip" Holmes, the recipient of the ACAMS AML/CTF Leadership in Government Award.

Cameron H. Holmes—nicknamed "Kip Holmes"— is the director of the Southwest Border Anti-Money Laundering Alliance and the senior litigator in the Criminal Division, Financial Remedies Section at the Arizona Attorney General's Office.

In 1981 Holmes joined the Arizona Attorney General's Office's then-new Organized Crime Project, a unit dedicated solely to prosecuting civil racketeering cases. He was the chief of the Financial Remedies Section from 1987 to 2008, and is now senior litigator in that section, which is a money laundering, forfeiture and civil RICO unit that concentrates on protecting legitimate commerce from the effects of financial fraud and money laundering through the disruption of such racketeering at its highest financial levels.

He has spoken on RICO and money laundering in 29 states, Mexico and Canada, has testified in legislative hearings on RICO statutes in the United States Congress and in several states, and was directly involved in the legislative process on Arizona forfeiture, money laundering, RICO and money transmitter/financial transaction reporting statutes, including the 1985 Arizona Money Laundering statute, the first in the nation, preceding the federal Money Laundering statute by a year. He was the primary draftsman of model RICO, forfeiture, money laundering, and money transmitter legislation for national use.

Holmes is the chair of the Arizona Forfeiture Association and the Arizona LECC Forfeiture Subcommittee. He is the author of numerous articles on racketeering, money laundering and forfeiture.

ACAMS Today: Can you tell us about RICO and why you originally became involved in RICO prosecutions?

Cameron "Kip" Holmes: It was Cambodia Spring (1970). I left Harvard determined to do something "relevant," in the language of the day. So naturally, I became a ghetto police officer. As an economics major, I looked around me at the money flows into and out of my district. Income was mostly the wages of its occupants, which were turned into consumer items, which were then turned into burglary and theft proceeds, which were then turned into drugs and consumed by the burglars and thieves. It was apparent that as long as the drug supplies persisted, capital formation was never going to be possible, government programs notwithstanding, because my district was a huge sieve, draining resources into the hands of outside drug suppliers—organized crime. I could see by 1971 that only a combination of economic remedies for criminal conduct would be effective to address the injustices I saw and prevent the blight on the lives of the people I was there to protect. I went to law school to learn to prosecute organized crime to control its economic effects on legitimate commerce. I went to Arizona to join the Task Force on Organized Crime formed after a newspaper reporter was murdered to stop his organized crime reportage. I then joined the Maricopa County [metro Phoenix] Attorney's Organized Crime Unit. When the Attorney General formed a civil RICO Organized Crime section in 1981, I knew I had found my natural home and joined as a charter member. I supervised the RICO/money laundering /forfeiture section for over 20 years, now serving it as Senior Litigation Counsel (graybeard).

You might say I am a simple person. I still have the same idea, the same goal, the same wife, and the same 1965 Volvo P1800 that I had in 1971.

AT: As an attorney what are the challenges you face when prosecuting an alleged criminal under the RICO statute?

CH: A RICO case differs from the prosecution of a one-off criminal event far more than in the fact that it generally requires a substantial dedication of resources. A RICO case requires the government to spend the time to understand the economic mechanism involved in the presenting problem. Formulating the problem not only guides the investigation, it molds the conceptualization of the "enterprise" for the prosecution, in light of the remedies that the government is seeking. The flexibility of the enterprise concept—under which the charged enterprise may be the perpetrator, the object of criminal acquisition, an instrumentality in the commission of other crimes, or a victim—obligates the government to consider its goals carefully and fit the case to the goals, rather than let opportunities or extraneous factors dictate the course of the case. RICO prosecution requires conscientious consideration of the likely outcomes and potential consequences to avoid unintended or inappropriate consequences, thoughts that rarely troubled me in my years as an organized crime prosecutor.

AT: What is the link between racketeering and money laundering?

CH: Money laundering is a direct descendant of racketeering and a catalyst that improves racketeering cases. The earliest U.S. money laundering statute, Arizona Revised Statutes §13-2317, enacted in 1985, grew out of a civil RICO unit at the Arizona Attorney General's Office called the Criminal Proceeds Recovery Project, formed in 1982. The goal was to focus civil RICO remedies on the proceeds of crime. The concept of operations was to concentrate on trafficking in stolen property to prevent and remedy property crimes by attacking facilitators—professional "fences." I was the prosecutor. The lead investigator involved in this project and I had also collaborated on a multi-year civil litigation applying Arizona's new RICO statute to a 19-location prostitution enterprise. That collaboration included the drafting and passage of a "prostitution enterprise" statute in Arizona whose goal it was to bring prior "receiving the earnings of a prostitute" law into the RCIO era. So in our eyes "receiving and concealing stolen property" was very similar to "receiving the earnings of a prostitute." Both criminalize the receipt of the proceeds of another crime— theft or prostitution. Both are aimed at financial facilitators of that underlying crime in an effort to attack that underlying crime more efficiently. What is surprising is both of these are ancient crimes recognized in most of the world, yet the distillation of the rationale on which they are based into a general money laundering offense is such a recent evolution.

The Criminal Proceeds Recovery Project supported its pleadings by reference to a book titled A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis, written by London Police Chief Patrick Colquhoun. Chief Colquhoun stated the trafficking in stolen property/facilitation idea very well when he wrote: "In contemplating the characters...of both [thieves and receivers of stolen property], there can be little hesitation in pronouncing the receivers to be the most mischievous of the two, inasmuch as without the aid they afford in purchasing and concealing every species of stolen property, thieves and robbers must quit the trade, as unproductive and hazardous in the extreme." Interestingly, Chief Colquhoun wrote that book in 1796.

After fermenting for 189 years, Chief Colquhoun's wise observations inspired the 1985 Arizona Money Laundering statute, conceived to take the next steps on the path to modern money laundering legislation by combining Chief Colquhoun's strategy of targeting financial facilitators to control the underlying criminal conduct with more modern RICO concepts. These opportunities for improvement included civil liability for organized criminal conduct, the advent of the "racketeering enterprise" concept of joint responsibility, and additional remedies such as enterprise-based forfeitures of the proceeds of crime. Adding money laundering to the list of "racketeering predicates" (federally known as Specified Unlawful Activity" (SUA)) applied the focus on the financial facilitation of crime to criminal conduct beyond theft. Most important, the new statute acknowledged the central importance of criminalizing "acquiring or maintaining an interest in, transferring, transporting, receiving or concealing the existence or nature of property" that is in fact the proceeds of racketeering "knowing or having reason to know" that it is the proceeds of some offense.

AT: What has been your most interesting case with regards to asset forfeiture?

CH: Asked to choose one case, it would be the seizure of $100 million from an account in a bank in North Carolina exactly one week after first hearing about the deposit of those funds into a different bank in New Jersey. This case came to me as a verbal SAR, followed by subpoenas, a written SAR, and close coordination with the banks involved. The Arizona connection was that the account holder stated the funds were borrowed using an Arizona gold mine as collateral. Unfortunately, he gave sufficient physical data on the mine's location for us to definitively find it. We found it to be virgin desert whose only improvement was an aging cattle loading chute. Arizona seized the funds for forfeiture on the theory that they were being used as a prop in an attempted fraud on the bank, a variant of a Prime Bank Instrument (PBI) scheme, in the absence of information proving that it was proceeds of a fraud. After the seizure, we learned that the account was the remains of about $420 million that had gone missing in the Bayou hedge fund collapse. Eventually, we wired $106 million to the U.S. Attorney in New York (the $6 million was interest, which was much better in those days) for distribution to the many victims. This case is the most interesting to ACAMS because it illustrates how effective close coordination between the private sector and government can be. Had we not seized the funds, the account holder was in the process of moving them offshore (the funds had already been in the UK, Germany, and Hong Kong), never to be seen again. No doubt one or both banks would then have been sued by purported PBI "victims" tracing "their" money to the bank(s).

AT: In what scenarios is asset forfeiture best utilized as a law enforcement tool?

CH: Asset forfeiture has evolved rapidly over the past thirty years, making it more versatile. The older model of civil in rem forfeiture remains, of course, the tool of choice to address assets whose ownership is unknown or whose owners are beyond the reach of our courts, as it was in the days of slave ships. This is often the case in bulk cash transportation seizures. In rem forfeiture it is also useful to take the profit out of a broader range of general crime because it is efficient if used thoughtfully.

The advent of substitute assets forfeiture has made civil forfeiture considerably more powerful because it obviates the need for tracing criminal proceeds to a particular asset. This bridges some of the gap that exists in the federal system between criminal in personam forfeiture and civil in rem forfeiture. In about a dozen states civil forfeiture is now available through in personam procedures as well as in rem procedures. When in personam liability is an option, whether by direct civil in personam statutes or by the substitute assets partial bridge, the financial remedies available can more closely match the societal harm because a judgment may be had against assets of the defendant that are not involved in any way in a crime, whether by facilitating a crime or by being traceable to a criminal act.

AT: Also, what changes, if any, does the private sector need to undertake to increase collaboration in asset forfeiture cases?

CH: Specifically focusing on asset forfeiture cases, the most useful procedural evolution for the private sector—interest holders of various interests in property alleged to be subject to forfeiture—would be to deal directly with the prosecutor at an early stage. By directly I mean through a person with immediate decision-making authority for the entity holding the interest, not an outside attorney. At the initiation of a large case, the prosecutor is trying to get a handle on all the assets under seizure, to understand what interests are involved in each item of property, and to prevent waste. If you can help with these, you may find that the prosecutor really wants to simplify the circumstances and is willing to accept creative suggestions. For example, you may receive a stipulation that your interest is exempt from forfeiture, so you don't have to file a claim at all. Your interest will be paid off when the asset is sold, if the government prevails. You may get possession of property and court permission to sell it in a commercially reasonable fashion to avoid storage fees and depreciation. In general, the prosecutor truly seeks to use financial remedies to protect legitimate commerce, and therefore wants to minimize any negative effects on legitimate commerce throughout the process. So pick up the phone at the first moment you know of the seizure. Many good things can come of it.

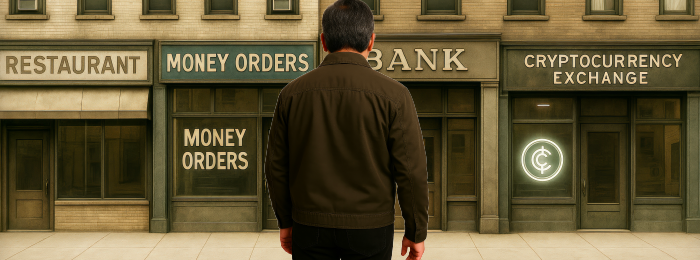

On the AML front, the private sector should recognize that law enforcement is often drawn into contact with the private sector around what I will call "hot spots" created by the shifting actions of criminal activity. These changes sometimes generate unusual economic opportunities for businesses that find themselves in a position to facilitate and benefit from the new activity. Small businesses operate on tight margins and some businesses are stressed by hard times. When greed and lack of moral character overcome them, some businesses are tempted to the dark side. The new market for money brokering on the Mexican border is an example, as are serving as money transmitters for Canadian lottery fraud, convenience store sales of meth precursors when small meth labs became profitable, and doctors' "pain management" pill mills during the oxycontin/oxycodone epidemic. Responsible members of the affected industries and compliance professionals are often early to recognize the signs of such hot spots. So are officers in the affected field of investigative specialty, such as drugs, fraud or money laundering. SARs provide a very useful bridge, but they are not enough by themselves to substitute for person-to-person meetings to exchange understandings of the economic mechanisms involved and their manifestations in the financial world. A proactive capacity to identify such hot spots and bring the stakeholders together early would make addressing these ever-evolving hot spots far more effective and ultimately less troubling to the private sector.

AT: As a long-time public servant with countless interactions with the private sector, what is your view on the overall commitment of the private sector to AML/Financial crimes?

CH: I believe that the overall commitment of the U.S. private sector to AML/financial crimes enforcement has made remarkable strides during my tenure in law enforcement. The very idea that money could be tainted by its source was not well accepted in 1970 when I got my first practical lessons in the finances of crime in the ghetto. In the late seventies bankers in Arizona were openly quoted in the press defending their bank's close financial relationship with organized criminals on the ground that "their money is as green as anyone else's." Looking back on those days, it is truly heartwarming to see the shift in attitude and the international scope of agreements on AML measures. Regrettably, recent investigations and prosecutions show that we have a long way to go. I believe that the next step for those institutions that have not kept up with the evolution is a concerted effort to build and maintain a robust corporate culture of compliance. No amount of policy and procedure writing by outside consultants will substitute for a top-down whole-hearted acceptance of compliance as a corporate imperative.

AT: What advice do you have for the public and private sectors on how they can better collaborate to fight racketeering and money laundering?

CH: I believe that the greatest challenge to the rule of law in the world today is the growing power of Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs), such as those now growing in Mexico and the Southwest. The best way to prevent TCOs' use of the world market process is to open it to view. Cutting off the outflow of illicit funds in countries such as Mexico by making their illegality and/or ownership transparent is directly related to accomplishment of the key goals of money laundering enforcement. Global transparency is therefore a core money laundering law enforcement goal, even more important than financial regulation alone because it goes directly to the usefulness of the illicit global financial system to organized criminals and creates investigative opportunities at the highest levels of TCO leadership. Simply put, global financial transparency will lead to the demise of the illicit dimension of the world market, which will lead to the demise of transnational criminal organizations, so it is the remaining anti-money laundering frontier.

As we rebuild after the current world financial crisis we must acknowledge the role of the shadow financial system in permitting that crises to occur and its continuing role in permitting organized crime to increase its global power. The global financial system is a man-made system for which people are accountable. The inescapable corollary of this observation is that law enforcement must accept a greater role in understanding and affecting the global free-market system if it is to be successful at controlling the TCOs. It needs private sector assistance to do this.

Much of what is now transpiring in Mexico is part of a larger international picture in which TCOs are making connections with other criminals on a world scale, with criminal host states, and even with terrorist organizations. While the challenge is immense, its solution presents an opportunity to move law enforcement, legitimate commerce, the intelligence community, the defense community, and the peoples and political unions they serve to new understandings of the nature of governance. Personal safety, civil liberties, property rights, rights to contract, international commerce, and the orderly and reliable protection of all of these are all under loosely coordinated attack. Our response will define a new social control era in human history that brings government and industry into fully functioning partnership, that transcends the stove-piped law enforcement and military models, that engages all wings of the intelligence community, and that becomes fully international. Much of the response of the forces of the rule of law will be guided by money laundering legislation and enforcement, which will necessarily focus on global illicit money flows and therefore on global financial transparency.

Interviewed by Karla Monterrosa-Yancey, CAMS, editor-in-chief, ACAMS, Miami, FL, USA, editor@acams.org