Author’s note: This is the second of two articles unraveling the complicated risk exposure that unregulated industries present to the regulated institutions that bank them.

Fintechs are somewhat of a buzzword today with numerous types of companies in various parts of the transaction flow—many entities dubbing themselves as fintechs simply if they can move the payments faster or farther. However, not all fintechs are alike and certainly not all present the same amount of risk to their core banking or financial institution (FI) partners. When the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) announced the fintech charter in July 2018, it was assumed that these fintechs would all sign up. However, as of December 2019, only 11 new charters were found on the OCC site and most of them were not fintech-related. Could it be because most of these fintechs are legally using the exemptions provided under the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) with regard to payment processors?

Technically, most fintechs are simply using existing payment rails, such as automated clearing house (ACH), to move money. These companies are also only responsible for one portion of the payment flow. This ACH movement—along with the purpose of moving the funds (payment for goods or services)—could qualify them as a nonmoney remitter at the federal level. Several administrative rulings from FinCEN provide various ways in which payment processors, payment facilitators, merchant payment companies and “agent of the payee” companies can take advantage of not qualifying as a money services business (MSB) under federal regulations and therefore not be subject to strict anti-money laundering (AML) programs. There is also a multibillion dollar “shadow lending” fintech market that is booming in the U.S. These lending products are offered through various means, some being underwritten by bigger banks, some being private lenders, but all without AML requirements.

This article addresses the various payment processors and fintechs that are also unregulated and expands the risk exposure to their respective banking partners. There are so many variations of fintechs as well as multiple portions of a transaction flow and varying transaction types that a fintech can leverage in order to speed up a payment or offer a payment process on behalf of merchants or e-commerce sites. Some examples of various fintech companies are listed below.

- Payment companies that facilitate the payout to sellers on various e-commerce sites (private sellers offer products with no inventory control)

- Payment processor, facilitators or aggregators that provide for a platform to rent or buy services (with no inventory control)

- Payment companies that facilitate payout of funds from collection-type sites (crowdfunding, event sites, etc.)

- Payment companies that underwrite or facilitate loans or alternative financing (shadow lending)

These all are described and addressed in the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF’s) money value transfer services (MVTS) guidance1 and their new payment products and services (NPPS) guidance.2 This short list is certainly not all-inclusive and it is likely a technology company will create a new payment method by the time this article is published.

What Is the Risk?

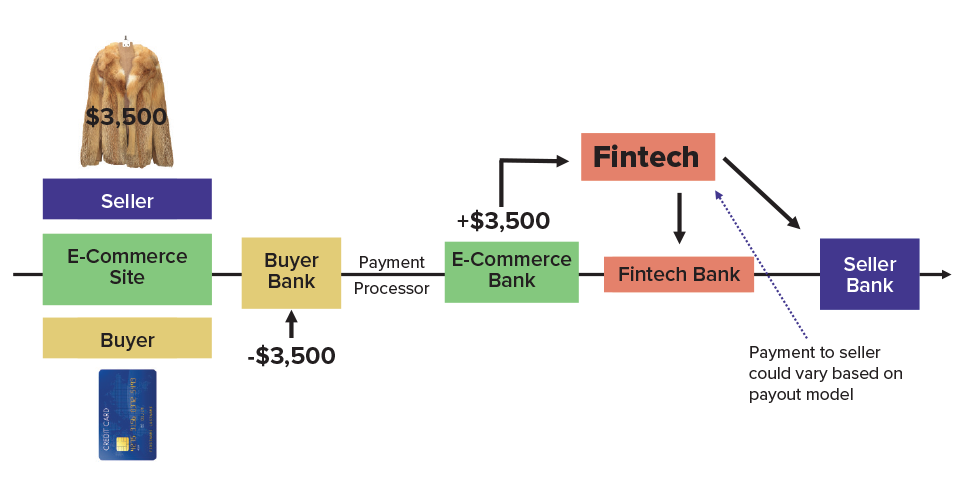

Some may read this and wonder what the risk is for both the U.S. and the banks that are providing the methods by which these fintechs are conducting business. The most high-level risk exposure can be summed up to one major issue, which is FATF’s main product-related risk factor: when the payment flow is divided up. For example, funds flow to, through and out of an e-commerce platform’s bank account. However, their primary banking relationship does not see all aspects of the other parties involved. Funds flowing out of an e-commerce’s account can be paid in batch form to a fintech firm, which then pays out funds to individuals on behalf of the e-commerce site (see example below).

New fintech payment flows break up the transaction from end-to-end, with some regulated parties and some that are not involved in the flow of the transaction. Depending on the rails (transaction vehicle type) that the fintech uses, they could use exemptions available under FinCEN rulings. From 2003 to 2014, there have been four published letters or rulings that could provide a variety of exemptions to fintechs as a whole or to a group of payment types within the fintech. For example, some fintechs offer various products to their customers like payment processing for e-commerce or brick-and-mortar stores. Some fintechs blend their offerings with payment processing, wallet-like products and money transmission. Some fintechs even provide payment processing in the form of loans. These payment types have an exemption under FinCEN. Within that fintech they could offer a remittance-like program, but because the program facilitates the payment of goods or services and utilizes the ACH system, they can claim exemption from federal AML requirements. Some states, mainly Florida, California and New York, may see this differently, so a fintech may use the “agent of the payee” status available in several states or may become a licensed remitter in that particular state. Fintechs that are savvy and are taking advantage of these exemptions and new definitions like “agent of the payee” are not doing anything illegal—they are using strategic advantages available through nascent regulations at the federal or state level. The following example may better clarify how not all products within a fintech could or would be regulated:

Again, some may wonder what is the net risk. When the banking partners onboard these fintechs, they request AML program information. The fintech should provide fully prescriptive, proactive monitoring requirements. However, if only a part of the fintech payment flows qualify as requiring AML oversight, then the partner bank may not have the time or knowledge it takes to understand a technology company and their various payment types. The larger risk is really for the country as a whole. A litmus test for these various fintech companies and their payment flows really comes when the product is rolled out to countries that are not the U.S. or Canada. If the payment product is rolled out in Europe or most countries in Asia, including Australia, the identical payment product or flow is considered fully under AML requirements. The AML Directives in the European Union as well as Financial Conduct Authority regulations in the United Kingdom do not provide an exemption to the Single Euro Payments Area which is equivalent to the U.S. National Automated Clearing House Association system. Regardless of payment rails—wire, ACH, check, cash, etc.—payment processors are treated as regulated institutions.

Money value transfer services and new payment methods have been accounted for in most other countries, outside of the U.S. This is evidenced by their regulations that require payment processing companies—which could be several different companies in one payment flow—to implement full AML compliance programs.

In the End, They Are All Payment Processors

Instead of using terms like merchant payment companies, third-party payment processors, payment facilitators, payment aggregators, merchant payment processors, fintechs or private ATM networks, the general term of payment processors should cover all aspects and parties to the transactions described below. While each of these vary with where they sit in the payment flow, most institutions will have some type of exposure to fintechs and payment processors (not deemed fintechs because they have been facilitating merchant payments for a while). Previously, it was mentioned that fintechs and payment processors are able to take advantage of loopholes and it is important to note that most of the legal loopholes were made available to old-school payment processing companies. It is worth noting here that any of these payment processors would have full AML regulations in most industrialized nations outside of the U.S. In order to avoid registering as an MSB or money remitter in the U.S., payment processors and fintechs can send/receive funds via ACH instead of wire. While this is not always a single elimination factor, it is important to know how ACH plays a role in the payments flow, as noted in the image on the right.

In addition to the aforementioned issues, it is vitally important for institutions to remember that merchant processing companies (companies that underwrite and issue card machines or e-commerce capabilities) do not have requirements to implement an AML program. When working with institutions that bank these merchant processing companies, it is interesting to note the amount of resistance from payment processors when this is mentioned. Most processors use fraud and risk monitoring as a substitute for money laundering monitoring. These are not one in the same, especially when it comes to payments monitoring. Several occasions over the past few years revealed payment processing companies that have an AML policy, yet were not registered as MSBs with FinCEN; therefore, they were not able to file the suspicious activity reports that are mentioned in their AML policy. This article is not meant to put merchant processing companies or payment processors in a bad light, as the fault is not theirs. They have what they are obligated to have under current U.S. requirements. Yet, most institutions maintaining relationships with these merchant processing companies are not taking the time to monitor the payment files or merchant types that the processing company is servicing. If the processing company is not monitoring for money laundering-related risks, then that greatly increases the risk exposure for the regulated institution that is allowing the processing company to use their rails to transfer funds via ACH.

It is important to remember that monitoring for fraud is an operational decision, meaning that there is not really a regulatory requirement to protect a company from fraud losses. Yet, it is done because the business does not want to go bankrupt. However, monitoring for money laundering is also currently not a requirement for merchant processing companies and because there is no benefit to that cost, it is not considered. Although some may be objecting to this description, monitoring for data like chargeback frequencies, deviations in average card swipes and deviations in monthly activity is not monitoring for money laundering or terrorist financing. Basic examples of monitoring reports that merchant processing companies should be employing to monitor for money laundering include high-risk industry code monitoring, average swipe value compared to the value of the product/service sold, multiple occurrences of the cardholder (when not normal for that business type) and total monthly dollar compared to the value of the product/service sold. To outline the differences between what merchant processing companies currently do (fraud monitoring) and what is needed (money laundering/terrorist monitoring), one can refer to the following scenario. A payment processor onboards a used car dealer in Florida. A broad background and credit check are performed on the owner as well as a review of the car dealer’s financial statement. The processing company issued two machines—one for car down payments as well as monthly payments with a projected average swipe of $500-$800 and one for the repair side of the business with a projected average swipe of $150. Weekly and monthly monitoring sessions are performed, looking for deviations in total projected activity and swipes, chargebacks, etc. Yet, when an AML professional reviews the activity and performs enhanced due diligence to include open-source investigations on the car dealer, there are red flags. The car dealer has just a few cars on the lot. In over 30 days it was noted there were no new cars on the lot, no new cars posted online and it was determined that the car dealer was not registered as a nonbank FI—a requirement under Florida law if the car dealer accepts payments for sold cars. The monthly total of swipes from both machines totaled well over $30,000, with no evidence—from the AML perspective—to support that income. This example of transaction laundering is a common one and is industry-agnostic. As long as there is no true inventory control, there is always room for misuse of the payment process.

Banks Are Left With the Risk

Most institutions are not monitoring merchants (business customers) who receive ACH deposits from payment processor networks simply because almost every business accepts debit or credit cards

So, if merchant processing companies are not monitoring for money laundering, then that leaves the current burden of responsibility on the regulated party yet again. Those would be the institutions that are banking the merchants (business customers) as well as those banking payment processors or fintechs. Most institutions are not monitoring merchants (business customers) who receive ACH deposits from payment processor networks simply because almost every business accepts debit or credit cards. Add in the fact that ACH transactions are the most used transaction type of all the transactions in any bank, on any given day. Bottom line is ACHs get buried. If the business customer is higher risk, then the customer may get a review of their overall income. Ideally, institutions are taking a critical look at the incoming ACH deposits from merchant card networks. But in actuality there are not many eyes on these payments—either from the payment processor (that makes money when swipes are performed) or from the institution that banks the merchant (business customer). From end-to-end, the only parties that really have a requirement to monitor for money laundering, granted several layers removed, would be the large issuing networks, but they only see their particular card network swipes at the terminal, and not all the swipes occurring at the merchant terminal.

Therefore, if the risk is greatly increased due to more parties to a transaction, because it dissects the flow from end-to-end and distorts the view, then a logical remedy would be to regulate the entities that have the most visibility. These entities would be fintechs and payment processors. Hopefully FATF explores the vulnerabilities in the U.S.’ payment processes as well as FinCEN’s exemptions during the next mutual evaluation. Of course, if the U.S. chooses to remove those exemptions and bring payment processors under AML requirements, then there would need to be enforcement measures with that action, which would require additional federal resources to perform examinations of these companies. From simple consumer to business, business to business, business to consumer payment flows (using the ACH system), to more complicated payment processors that provide loan or shadow financing fintech products, the U.S. needs to re-evaluate the vulnerabilities in the hundreds of billions of dollars that flow essentially unmonitored through the U.S. ACH system.

- “Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach: Money or Value Transfer Services,” Financial Action Task Force, February 2016, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-RBA-money-value-transfer-services.pdf

- “Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach: Prepaid Cards, Mobile Payments and Internet-Based Payment Services,” Financial Action Task Force, June 2013, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/Guidance-RBA-NPPS.pdf