As discussions on sustainability continue to push toward center stage in the corporate world, the time has come for anti-money laundering (AML) professionals to reassess their day-to-day responsibilities through the lens of environmental, social and governance (ESG) targets so that they can not only be included in the burgeoning movement but furthered because of it.

Evaluating or even charting progress on the sustainability front across ESG is an evolving practice

The importance of incorporating a sustainable mindset in conducting business has been articulated in many ways but none more concisely than that of Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever, when he stated, “businesses cannot succeed in societies that fail.”1 This short, blunt statement manages to encapsulate and merge both social and shareholder responsibility as the rationale for adopting a sustainable approach; concepts some could argue were not always viewed with congruency. Furthermore, Polman, who has written and spoken extensively on sustainability, has also contributed toward a widening of what sustainability means within an industry, including concepts of inequality and racial tension in his discussions. Lastly, and integral to this article’s argument, Polman has cited lack of leadership as one of the main hindrances to effective implementation of sustainable practices and challenges corporate leaders to show courage through leadership, even in the absence of governmental trendsetters.2 The issue—let alone the solution to sustainability—is complex and requires dynamic societal contributions to solve. However, this article will explain how and why AML professionals’ contribution is much needed as it will be argued that it is inherently sustainable in its application.

What is ESG?

To begin, the definition of the term “sustainability” is important to this discussion and, while it varies slightly, within this context, it describes meeting one’s own needs “…without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”3 Conversely, the acronym ESG, while sometimes used interchangeably with the term sustainability, is more focused on establishing a framework for ensuring progress is made. It outlines the three spheres of importance that are integral to ensuring that such a compromise of future generations, as described above, does not occur.

To further break down what each area of ESG captures, they are traditionally grouped, as shown below.

The E (environmental): energy efficiency, greenhouse gas emissions, carbon footprint, preservation of forest and water life, chemical use, etc.

The S (social): considerations ranging from factors such as staff turnovers, workers’ rights, how the staff is treated, if they are paid a decent wage, how a country/corporation is respecting human rights, gender diversity, workers' health and safety, social impact on the society, etc.

The G (governance): corruption, management of the firm, board members and leaders in the corporation, litigation risks, risk management, historical conflicts and the companies’ ability to handle and solve them, etc. Academic studies have shown that strong environmental and social standards stem from a good governance structure, which is why it is of great importance.4

Can It Be Measured?

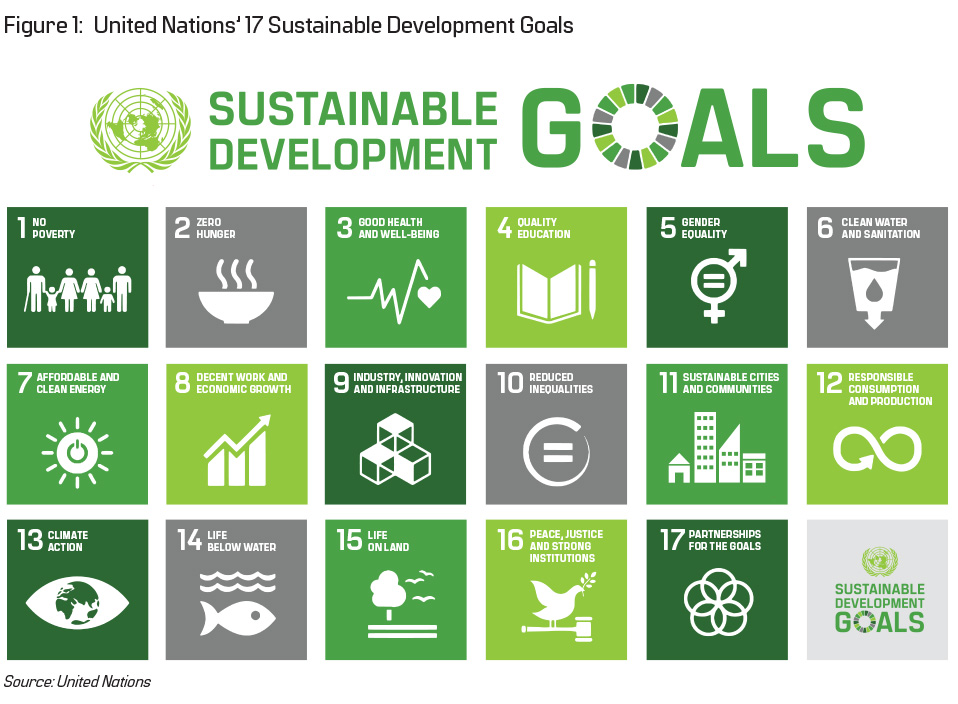

Evaluating or even charting progress on the sustainability front across ESG is an evolving practice. However, to date, the main guiding compass in this space has been the United Nations’ (U.N.) 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were adopted in 2015.5 The SDGs build upon the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted by the U.N. in 2000 and ended in 2015.6 The SDGs are promoted as a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all, as they address a wide array of issues that range from poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation as well as peace and justice (see Figure 1).7 Inclusive of the 17 SDGs are a total of 169 targets spread across the goals to provide more guidance on how to obtain sustainability. However, while these goals and respective targets have been internalized by many corporations, their application is still largely voluntary and their implementation difficult to assess. These challenges are, in part, what inspired many leading CEOs to call for implementation and assessment. A call heeded by the World Economic Forum (WEF) with their work on measuring stakeholder capitalism to allow for more common metrics and consistent reporting of sustainable value creation.8

AML and Sustainability

Looking at the financial services industry, particularly modern banking, across its historical timeline from its birth in 17th century England to today, the practice and profession of AML within the banking world is still a relatively new phenomenon.9 Bedrock legislation that gave birth to the profession and practice of AML started with the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), and arguably it did not expand internationally with vigor until after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Cumulatively, these important pieces of AML legislation, such as the BSA, USA PATRIOT Act and Canada’s Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, and similar others, are designed to safeguard financial systems from criminality such as drug trafficking, organized crime and terrorist financing and, by virtue, the societies in which they operate. It is important to note that these legislative efforts, while both morally right and sustainably minded, were not initially without their critics, with several lawsuits being launched against the passing of the BSA citing an infringement of the Fourth Amendment, which protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. One of the most notable lawsuits was filed by the California Bankers Association, where the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled against them, stating that the BSA did not infringe on the Fourth Amendment.10

The introduction of ground-breaking AML legislation predates the formal conversation of corporate sustainability by decades, in some cases, but in many ways, it derives from the same intent to encourage (and in some cases force) corporations to undertake measures that protect the societies for which they operate for future generations.

Advancing the Role of AML Within Sustainability Initiatives

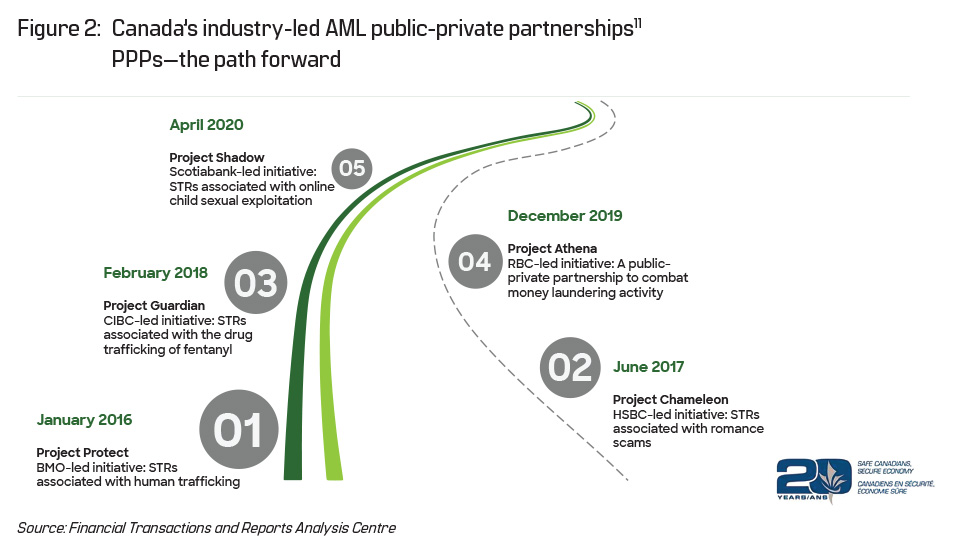

Inherently, the practice of AML is sustainability in action within the governance arena of ESG. This is how AML has been bucketed by many financial institutions within their annual sustainability reports since their inception. However, as AML evolves, it has begun to expand its applicability to that of social and environmental as well, but only when the application of AML is proactive as opposed to passive. Passive AML is the baseline regulatory implantation of controls required, while proactive, in this context, refers to efforts undertaken to focus on areas of interest under the ESG mantra. For example, Canada’s industry-led public-private partnership model to combat unique financial crimes, which disproportionately affects marginalized and vulnerable individuals or serves to undermine the AML regime of the country through the implementation of AML practices, is a prime example of proactive AML (see Figure 2). This public-private partnership series has been leveraged to tackle a range of topics from human trafficking to online child exploitation, to elder abuse. The efforts can be categorized under the social category, as opposed to the governance category within ESG.

In Scotiabank’s 2020 ESG Report, it is noted, “through our participation and leadership in public-private partnerships, like Project Shadow, Scotiabank is helping to shine a spotlight on the dark nature of online child exploitation and its criminal use of the financial system. Our collective efforts to increase awareness, identify typologies and facilitate reporting to law enforcement will make an immeasurable difference to those communities that we serve.”12

Looking Forward

AML’s role within sustainability is undeniable from its inception to the present; however, its inclusion within the broader conversation of sustainability still requires the effort from AML professionals through awareness, collaboration and initiative. In looking ahead, AML can lead on addressing sustainability issues encapsulated within many of the SDGs’ 17 goals, such as gender equality (goal 5) and life on land (goal 15). An example of the aforementioned goals is the work undertaken by the Lichtenstein Initiative on their financial access project for survivors of human trafficking13 and ACAMS on their environmental crimes awareness work.14 Through both passive and proactive approaches, AML will contribute tangibly to sustainable initiatives over the next decade and beyond.

Stuart Davis, CAMS, executive vice president, global head, financial crimes risk management and chief anti-money laundering officer, Scotiabank, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, sdavis@scotiabank.com

Joseph Mari, CAMS, director, financial intelligence unit and external partnerships, Scotiabank, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, joseph.mari@scotiabank.com

- Deonna Anderson, “Paul Polman: ‘Businesses cannot succeed in societies that fail,’” GreenBiz, July 22, 2020, https://www.greenbiz.com/article/paul-polman-businesses-cannot-succeed-societies-fail

- Ibid.

- “What is sustainability?” University of Alberta Office of Sustainability, https://www.mcgill.ca/sustainability/files/sustainability/what-is-sustainability.pdf

- Mia Söderberg, “Putting ESG and sustainability into perspective in Manager Selection,” Global Fund Search, https://globalfundsearch.com/blog/esg-sustainability-investing/

- “The 17 Goals,” United Nations, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- “Millennium Goals,” United Nations, https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

- “Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals,” United Nations, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- “Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation,” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/stakeholdercapitalism

- Prachi Juneja, “History of Modern Banking,” Management Study Guide, https://www.managementstudyguide.com/central-banking-in-united-states.htm; Jongchul Kim, “How modern banking originated: The London goldsmith-bankers’ institutionalisation of trust,” Business History Issue 53, Volume 6, pages 939-959.

- “California Bankers Assn. v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974),” Justicia, 1974, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/416/21/

- Brian Monroe, “Regional Report: Canada has done ‘amazing things’ to fight crime through public-private partnerships, but still hampered by stringent privacy rules, lack of AML safe harbors,” Certified Financial Crime Specialists, August 25, 2020, https://www.acfcs.org/regional-report-canada-has-done-amazing-things-to-fight-crime-through-public-private-partnerships-but-still-hampered-by-stringent-privacy-rules-lack-of-aml-safe-harbors/

- 2020 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Report,” Scotiabank, https://www.scotiabank.com/content/dam/scotiabank/canada/en/documents/about/Scotiabank_2020_ESG_Report_Final.pdf

- “Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking,” Liechtenstein Initiative, https://www.fastinitiative.org/

- “Green Crime: Re-Thinking How Financial Crime Strategies Apply to Environmental Crime,” ACAMS, September 2021, https://www.acams.org/en/green-crime-re-thinking-how-financial-crime-strategies-apply-to-environmental-crime?utm_source_code=4147&utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=social#summary-e1a3ce77