Organ transplantation is a medical phenomenon that began in the middle of the 20th century. It restores an individual’s wellbeing and capacity for a productive life and brings immeasurable relief and joy for their families and friends. The notion of a second chance at life based on a kaleidoscope of factors has enabled this ultimate gift to occur, the gift of life through transplantation. Yet a dark side has emerged alongside these acts of kindness. These acts of humanity have come at a cost and that cost is organ shortages. As a consequence of this shortage, approximately 10 percent of all organ transplants conducted annually around the globe are a result of organ trafficking and transplant tourism.1

In 2008, during a groundbreaking summit in Istanbul, a blueprint was developed to guide government leaders, medical professionals, and legal experts and ethicists who would be tasked with combating a medical practice that tragically illustrates the social injustice that exists in the world. In the preamble of the Declaration of Istanbul, the authors re-stated a 2004 World Health Organization call to action, “to take measures to protect the poorest and most vulnerable groups from transplant tourism and the sale of organs and tissues, including attention to the wider problem of international trafficking in human tissues and organs.”2

Project Organ Begins

With every passing year, there is an expanding body of research and understanding about the world of organ trafficking and transplant tourism. From an anti-money laundering (AML) perspective, this awareness was raised considerably in a comprehensive article published in June 2018, by Christina Bain of Babson College, Joseph Mari of BMO Financial Group Major Investigations Team and Dr. Francis Delmonico of Harvard University Medical School. At the conclusion of this article, a clarion call was made to society at large: “In order to effectively combat organ trafficking and also raise its visibility among other forms of transnational organized crimes, it is vital to engage in public-private sector partnerships. The private sector, including the financial industry, can be essential in this global fight.”3 Project Organ began in earnest. It is critical for the international AML community to respond with as much consensus and coordination as possible. Despite the unique and difficult circumstances that Project Organ may encounter from an AML perspective, organ trafficking can and should be addressed.

Academia as Partners

AML professionals need to be aware that as with other forms of crime involving finances, there are as many monetary-based variables that allow it to occur as there are to detect and combat it. The actual transplantation is not a complicated venture but the preceding and ensuing financial aspect will be difficult to detect. One can look to criminological theory to illustrate how it happens and how it may be stopped. The routine activity theory has utility in that it assists in demonstrating the cause and effect relationship that must inevitably occur. In 1979, Professors Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson developed a framework in which situational crime prevention could conceivably work.4 In this framework, Felson and Cohen theorized that in order for a crime such as organ trafficking to occur, there must be a suitable target (the living or deceased organ source), an offender in greed (associated organ broker networks) and the absence of a capable guardian (effective government, law enforcement and legislative frameworks). Although originally intended as a temporal and spatial-oriented theory, it has also been easily adapted to emerging threats such as cybercrime. The solution to organ trafficking and transplant tourism within the AML matrix must inevitably come from high levels of collaboration, intense usage of data and a keen awareness of the required landscape needed in a holistic sense, to combat this phenomenon. Specifically, there must be collaboration between transplant professionals and government authorities that can combat organ trafficking and transplant tourism. Through additional collaboration between transplant professionals and the banking industry, a better assessment can be made as to the financial aspect of this medical procedure and the large sums of money required to facilitate the transplant in foreign locations.

In broader strokes, the AML industry must align itself with other efforts to effectively detect and combat organ trafficking. As with any industry-centric effort, there must be advocates and leadership that help foment action and energy to push initiatives forward. Peter Warrack, formerly of the Bank of Montreal and now chief compliance officer of Bitfinex, and Timea Nagy, survivor and activist, are seminal voices in the Project Protect movement. Their efforts spawned action that made integrated approaches to human trafficking possible and in relative terms successful given the innate challenges they faced.5

A Protocol Critical to Success

The first priority of AML professionals must be aligned with a larger government effort to deal with this phenomenon. In 2011, such guidance was created by a number of advocates dedicated to the eradication of organ trafficking. Led by Dr. Francis Delmonico and associates at the World Health Organization, A Protocol of Government Action to Develop National Self Sufficiency: Self Sufficiency in Donation and Transplantation was created. In this document, the writers sought to emphasize the responsibility of governments in providing resources so that organs for transplantation could be available from the deceased. In addition, it sought to provide guidance and leadership to governments to ensure organ trafficking was minimized as well as setting a framework to enable governments to support organ transplantation. In order to create more equitable donor and recipient systems and individual country self-sufficiency, the Protocol emphasized the importance of utilizing organs and resources within a country first and foremost. There was a consensus that if governments abdicate this responsibility, it enables illegal practices by compelling individuals to find organs from those who would sell them in foreign destinations.6

This Protocol also codifies a government blueprint to legitimize organ harvesting and transplantation within national borders. Through intense scientific and medical rigor and a pronounced effort to ensure equality, the Protocol seeks to remove predatory people and agencies from the environment. In essence, the Protocol would disrupt the trade by ensuring there is a capable guardian and thus remove one of the three critical pieces of Felson and Cohen’s crime theory.

In addition, the Protocol seeks to leverage a robust nationalistic and inclusive approach that will remedy the ineffective and narrow punitive approach criminalization takes. In an informing study of the organ trade in Egypt, Professor Seán Columb delved into the organ trade of Sudanese populations within that country. His research asserts that the criminalization of the organ trafficking trade, on its own, simply drives the organ market deeper into the shadows, rendering enforcement and prevention more difficult.7

“Human rights are not only violated by terrorism, repression or assassination, but also by unfair economic structures that creates huge inequalities...."

– Pope Francis

Legislative Assistance

In a first of its kind in Canada, and aligned with the Protocol, Garnett Genuis, a federal member of Parliament, tabled a private members bill that seeks to outlaw organ trafficking by Canadians or those who are found within the country. This bill was originally tabled in 2015, but was introduced again and had its first reading in 2017. The bill sets out to criminalize financial efforts to obtain an organ from an unwitting donor as well as the actual acquisition of an organ. If successful, this bill would become law and give greater leverage to law enforcement and regulatory agencies to detect and enforce illegal organ trafficking within the country or in relation to it.8

In tandem with the private members bill by Genuis in the House of Commons, Canadian Senator Salma Ataullahjan gave second reading to a similar bill that would outlaw organ trafficking and also bar landed immigrants from coming into Canada if they are involved in the illicit organ trade. As both bills are in both Houses of the Canadian Parliament, it bodes well that Canada will join the list of countries who specifically outlaw this practice.9

Multidisciplinary Partnerships Needed

The key to any success for AML professionals, particularly in financial institutions, is to form, nurture and enhance public-private partnerships like Project Protect did. Having a robust and vibrant dialogue between financial institutions, financial regulators and law enforcement agencies is mission critical to ensuring the enforcement side of this effort is working to its full potential. In his address to a U.S. Intelligence symposium, former Interim Director of Canada’s Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) Barry MacKillop said our operations are based on a “compliance for Intelligence and Intelligence for Enforcement, a concept which recognizes that the production of financial intelligence is a continuum.”10 The existence of clear and evidence-based indicators of organ trafficking will lead to actionable guidance to all financial institutions who in turn will report on transactional activity to national regulators.

Exploiting Financial Indicators of Organ Trafficking

The development of financial indicators of organ trafficking will be the central effort of the AML community moving forward. These indicators must not only be developed within each financial institution but also through rigorous and robust research done internationally. Organ trafficking, like labor- and sexual-slavery-based human trafficking, is an international crime and requires deep insights into transnational dynamics. Exploring and researching raw data will enhance and inform the transactional models financial intuitions will use to search for evidence of organ trafficking within their transactional data systems. This crime centers on organs for money. Following the money in the information age is difficult and at times impossible. To enhance this effort, financial institutions, law enforcement, government regulatory agencies, advocates, the medical/science community and academic researchers must join forces to extract a more fulsome picture of this crime. The law enforcement community has moved significantly toward evidence-based approaches to crime reduction and prevention. The establishment of Societies for Evidence-Based Policing, organizations where membership is drawn from multiple stakeholders partnered around the most current criminal justice research, have become more commonplace in the areas of crime prevention and reduction strategies globally. As research partners, they are getting stronger.

The establishment of research working groups composed of the above parties will enhance the effort Project Organ requires moving forward. Major interest in human trafficking has been taken by prominent groups such as the Pontifical Academy of Social Studies in Vatican City. Leveraging the influence of such groups and their significant scientific capabilities will buttress the effort. Other industry-centered bodies such as national medical and doctor associations, life and health insurance associations as well as other agencies like border patrol and customs agencies must also have input and maintain a line of sight into organ trafficking detection and prevention efforts. One of the key deliverables that will assist financial institutions is comprehensive research into typological trends relating to organ trafficking and transplant tourism. By connecting existing research, law enforcement data on organ trafficking cases and other sources of information, a more expansive statistical baseline will emerge. Typological trends relating to the following will inform the larger effort and also individual efforts:

- Typologies of organ recipients

- Typologies of organ hosts

- Typologies of organ trafficking facilitation groups

- Financial transaction typologies between the recipient to the organ trafficking facilitation groups

- Financial typologies of organ recipients (source of payment and funds)

- Typologies of payments to organ hosts (if any)

- National and international typologies of affected countries involved in the organ trade

- Typologies of legal regimes focused on the organ trade

- Socio-demographic analysis of organ recipients and hosts

- Comparing and contrasting research as it relates to specific organs

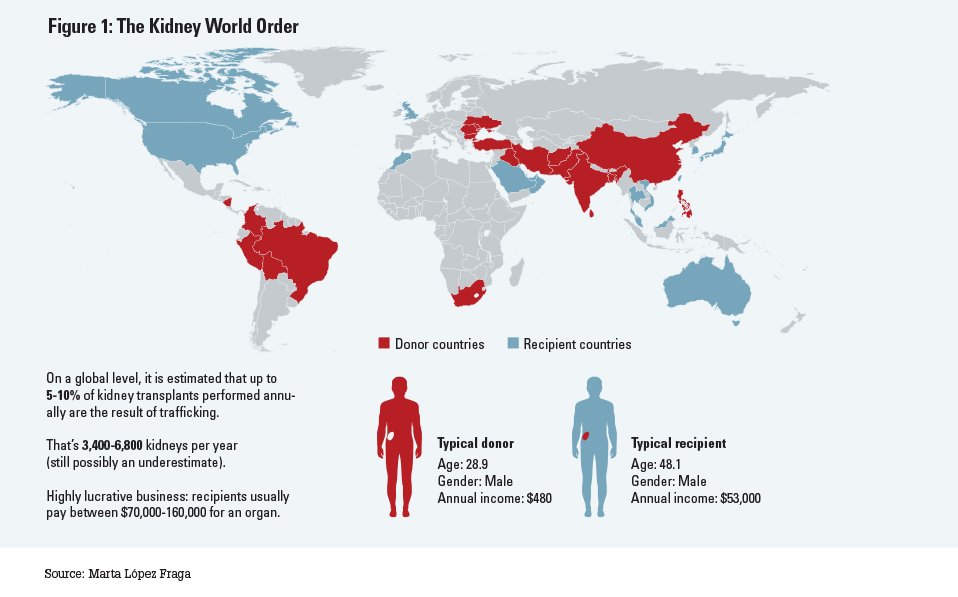

The infographic below illustrates the need for further scholarship. In general, males are both recipients and donors. Research indicates it affects women as well in certain parts of the world.11

In addition to the above avenues of inquiry and scholarship, the methods of payment must be vigorously studied to aid and assist AML professionals. The role of cryptocurrency, hawalas, wire payments, email money transfers and large cash withdrawals all must be exploited and examined for trends and recurrence in various emerging patterns of activity. In this effort, research must lead the way.

A Call to Arms

One of the foundational strategies that would assist this effort is requiring doctors to be obligated to report instances in which an individual underwent organ transplantation in a foreign destination to government authorities. The government would then initiate an investigation and determine if potential large monetary transactions occurred and were associated with the transplantation. The participation of the medical community is critical in this initiative.

Moving forward, this effort will rely on many stakeholders: survivors, industries, universities, government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and community leaders. Survivors should always be included and consulted. Oftentimes law enforcement or medical professionals are the first to come to the aid of an organ host. A structured approach must be applied whenever possible to glean as much intelligence to inform the effort.

This article seeks to build on the exceptional efforts of those tasked with combating human trafficking that now includes organ trafficking as part of this global fight, which requires leadership above all else. AML professionals have a unique vantage point and have access to financial indicators that no other group has presently. Groups such as ACAMS and other industry-specific organizations must step into place and lead this initiative. Local, regional, national and international research working groups need to tackle this elusive phenomenon and should be formed and encouraged. Linkage between these groups will be critical and can be facilitated through international banking groups, national financial intelligence units, law enforcement groups such as INTERPOL and the International Association of Chiefs of Police, and international academic forums dedicated to shedding light on crimes such as this.

Organ trafficking, like labor-

and sexual-slavery-based human trafficking, is an international crime and requires deep insights into transnational dynamics

Most importantly, this effort must always center on the survivors of organ trafficking. It is for this community, who is largely economically disenfranchised, marginalized, desperate and unprotected by those entrusted to do that very service, that efforts must be rededicated and redoubled. Through tireless leadership and advocacy, robust partnerships, scholarship, dedication to enhancing human rights and good corporate citizenship, AML professionals can arc the response to organ trafficking and significantly impact the lives of others one more time.

- “The implications of Istanbul Declaration on organ trafficking and transplant tourism,” Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation, April 2009,

https://journals.lww.com/co-transplantation/Fulltext/2009/04000/The_implications_of_Istanbul_Declaration_on_organ.3.aspx - “The declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking and transplant tourism,” Indian Journal of Nephrology, July 2008,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2813140/ - Christina Bain, Joseph Mari and Dr. Francis L. Delmonico, “Organ Trafficking: The Unseen Form of Human Trafficking,” ACAMS Today, June 2018,

https://www.acamstoday.org/organ-trafficking-the-unseen-form-of-human-trafficking/ - “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach,” American Sociological Review, 1979, Vol. 44, pp. 588-608,

http://www.personal.psu.edu/users/e/x/exs44/597b-Comm%26Crime/Cohen_FelsonRoutine-Activities.pdf - “The Disrupters: Tracking the Traffickers,” The Economist, 2018, http://eydisrupters.films.economist.com/ey-disrupters

- “A Protocol of Government Action to Develop National Self Sufficiency: Self Sufficiency in Donation and Transplantation,” The Lancet, October 15, 2011, p. 378.

- Seán Columb, “Excavating the Organ Trade: An Empirical Study of Organ Trading Networks in Cairo, Egypt,” The British Journal of Criminology, 2016, https://academic.oup.com/bjc/article/57/6/1301/2623947

- “An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (trafficking and transplanting human organs and other body parts),” Parliament of Canada, April 10, 2017, http://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/BillDetails.aspx?Language=E&billId=8870309

- “Senate of Canada BILL S-240: An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (trafficking in human organs),” Parliament of Canada, October 31, 2017, http://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/S-240/first-reading

- “Remarks by Interim Director Barry MacKillop Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada at the US

Parliamentary Intelligence-Security Forum,” Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada, December 7, 2017,

http://www.fintrac-canafe.gc.ca/new-neuf/ps-pa/2017-12-08-eng.asp - John Irvine, “Desperate Syrian refugees selling their organs to finance travel to Europe,” ITV News, June 19, 2018,

http://www.itv.com/news/2018-06-19/refugees-selling-organs/